記事見出し

- The ink-making industry of Koubaien began in the late Muromachi period.

- Successive Heads of Kobaien

- Founder: Matsui Michinori (1528–1590) [Official Title: Tosa no Jo]

- Second Generation: Matsui Michiyoshi (1578–1661) [Official Title: Tosa no Jo]

- Third Generation: Matsui Michitoshi (1611–1697) [Official Title: Izumi no Jo]

- Fourth Generation: Matsui Michiyoshi (1640–1711) [Official Title: Tosa no Jo]

- Fifth Generation: Matsui Motonori (1660–1719) [Official Title: Echigo no Jo]

- Sixth Generation: Matsui Motayasu (1689–1743) [Official Title: Izumi no Jo]

- Seventh Generation: Matsui Motoi (1716–1782) [Official Title: Izumi no Jo]

- Eighth Generation: Matsui Mototaka (1756–1817) [Official Title: Izumi no Jo]

- Ninth Generation: Matsui Motozuru (1799–1857) [Official Title: Izumi no Jo]

- Tenth Generation: Matsui Motonaga (1828–1865) [Official Title: Tosa no Jo]

- Eleventh Generation: Matsui Motoyasu (1862–1931)

- Twelfth Generation: Matsui Teitaro (1884–1952)

- Thirteenth Generation: Matsui Motohisa (1913–1967)

- Fourteenth Generation: Matsui Gensho (1964–1997)

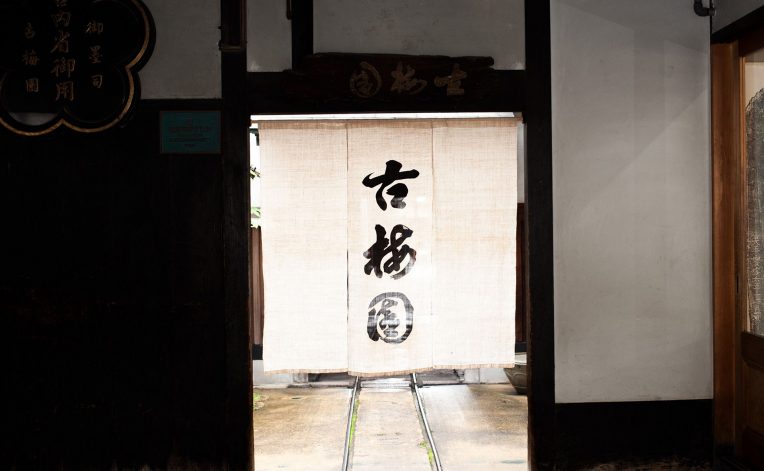

The ink-making industry of Koubaien began in the late Muromachi period.

The founder, Matsui Michinori (1528-1590), received the official title of Tosa no Jo. The second generation, Michiyoshi, also received the title of Tosa no Jo, and this title was passed down through generations. The third generation, Michitoshi (1611-1697), had a preference for plum blossoms and planted many plum trees under the eaves, leading people to refer to it as Koubaien. The son of the fourth generation, Michiyoshi (1641-1711), named Motonori, had an interest in academics and studied under Ito Jinsai. According to “Shokajin Butsushi” (1792 edition), “Matsugetsu Motonori, also known as Toan. A ink artisan from Nankin. He enjoys elegance and associates with distinguished families. He compiles family ink genealogies and presents them to refined guests or exchanges them for poetry. Koubaien has been known through generations.” He was known as a merchant-scholar and a Han poet who published “Toan Shikou,” a collection of his poetry. Additionally, he devoted himself to the study and improvement of Japanese ink, a legacy continued by the sixth generation, Motayasu.

Motayasu (1689-1743) is introduced in “Kokin Bokuseki Kantei Benran” (1855 edition) as follows: “His name is Motayasu, and his pseudonym is Teibun. He is also known as Gengen Sai. He is an ink artisan from Nanto. He is commonly referred to as Iwai no Jo. He inherited his father Toan’s scholarly pursuits and was skilled in poetry. Motayasu succeeded his father’s Miniku and once communicated with Tang to learn two techniques of ink production from that country. He refined his ink according to these methods. Later, during the Genbun era, he received official permission and traveled to Nagasaki, where he observed the ink-making methods of the Qing people and refined his techniques further. Motayasu was highly skilled in calligraphy.”

Motayasu’s efforts to explore Chinese ink-making techniques are also evident in various parts of the “Ink Genealogy,” but his journey to Nagasaki in the year Genbun 4 (1739) is particularly notable. He obtained official permission and engaged in question-and-answer sessions about ink-making techniques with nine Chinese residents in Nagasaki, leaving behind a handwritten record titled “Notes on the Dialogue of Chinese Ink Production.” Additionally, there is a handwritten document titled “Enki-shiki Bokuhon Shikou,” which explores the origins of Japanese ink production. Furthermore, he compiled “Meiboku Shin-ei” (or “Koubaien Meiboku Shin-ei”), which gathers poems dedicated to “Toyoyama Kouboku” (or “Toyoyama Fragrant Ink”), and published it in the year Shotoku 2 (1712). He also collected poems contributed by Qing people and compiled them into “Daiboku Kouko Shishuu,” published in the year Kyoho 19 (1734).

These books on ink demonstrate deep appreciation for literary arts and a passionate dedication to the ink-making industry. However, the pinnacle of expertise lies in the “Ink Genealogy” and “Kobaien Ink Discussions.” The seventh generation, Motozumi, continued his father’s legacy and created “Benibana Sumi” (or “Benibana Ink”) mixed with safflower. He also inherited his father’s “Ink Genealogy” and compiled the “Second Volume.” In summary, spanning three generations from Motonori to Motayasu to Motozumi, Kobaien made significant advancements in ink-making and left valuable research achievements in the history of ink.

Successive Heads of Kobaien

Founder: Matsui Michinori (1528–1590) [Official Title: Tosa no Jo]

Having served Nakahara Tochuu, the lord of Jyuuichi Castle in Yamato Province, Michinori relocated to Nanto (Nara) in 1577 and started the ink-making business. At that time, the ink-making industry in Japan was still immature. Through studies based on texts such as the “Enki Shiki Ryo Zoumoku Shiki,” “Li Family Ink Making Method,” and “Kukai Nitai Bou Oil Smoke Making Method,” he developed methods for producing high-quality ink. In 1603, he presented high-quality ink to the Imperial Court, for which he was granted the title “Tosa no Jo” in recognition of his achievements. He was commonly known as Matasaburou.

Second Generation: Matsui Michiyoshi (1578–1661) [Official Title: Tosa no Jo]

There was an old plum tree in the corner of his home garden, which received praise from visiting literati and ink connoisseurs. Thus, the garden name “Kobaien” was born, inspired by the old plum tree. The inscription on a paulownia box reads “Kobaien, crafted by the first patriarch,” suggesting that the second patriarch, Michiyoshi, created the garden name “Kobaien.”

Third Generation: Matsui Michitoshi (1611–1697) [Official Title: Izumi no Jo]

He received appointments from the Tokugawa Shogunate, stationed in Edo, and undertook missions at daimyo residences.

Fourth Generation: Matsui Michiyoshi (1640–1711) [Official Title: Tosa no Jo]

Fifth Generation: Matsui Motonori (1660–1719) [Official Title: Echigo no Jo]

He studied under the Confucian scholar Itou Jinsai, adopting the pseudonym “Toan.”

Sixth Generation: Matsui Motayasu (1689–1743) [Official Title: Izumi no Jo]

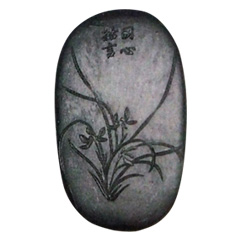

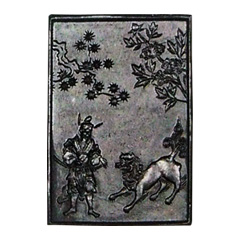

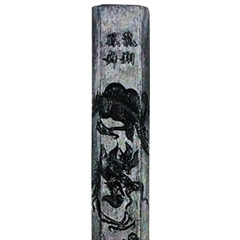

Sixth Generation: Matsui Motayasu (1689–1743) [Official Title: Izumi no Jo] Also known as Genjou-sai Teibun. In 1739, he obtained permission from the shogunate and formed friendships with Chinese ink artisans such as Cheng Tengmu and Wang Junkai in Nagasaki, facilitating technical exchanges between the two countries. Subsequently, he authored works such as “Kobaien Mokufu Shikou” (Records of Kobaien’s Ink Genealogy, Four Volumes),

“Kobaien Mokudan” (Discussions on Kobaien’s Ink), and “Bokuwashi,” among others. The woodblock diagrams in the four volumes of “Kobaien Mokufu” include examples still produced today, such as “Hakkaku Rojomatsu” (Octagonal Old Pine), “Shakyou Sumi” (Sutra Ink), “Gyokuran” (Jade Orchid), and “Daizai Hotei” (Greatly Blessed Hotei). The ink created by Motayasu, the pioneer of Kobaien’s revival, sought to improve Japanese ink-making. In 1739, with official approval, he exchanged ink-making techniques with Chinese ink artisans in Nagasaki, producing high-quality ink representative of that era.

Seventh Generation: Matsui Motoi (1716–1782) [Official Title: Izumi no Jo]

Upon the orders of his father, Motayasu, he experimented with safflower ink, successfully completing the “Kobaien Ink Genealogy, Volume Two,” and authored it. Thereafter, the term “ink = Kubaien” became synonymous, gaining widespread popularity. The “Ink Genealogy, Volume Two” includes ink varieties such as “Gochi,” “Chikurin Shichiken,” “Shinsen,” “Benibana,” “Inchu Hassen,” and “Gen no Mata Gen,” which are still produced today.

He authored the “Kobaien Ink Genealogy, Volume Two” and created a renowned ink called “Benibana Ink” for calligraphy. He also created ink for painting through interactions with Chinese artisans, contributing to the era’s prestigious ink varieties.

Eighth Generation: Matsui Mototaka (1756–1817) [Official Title: Izumi no Jo]

Bestowed with the official title “Izumi no Jo,” he continued the family’s ink business under the peaceful and prosperous atmosphere of his era.

Among the renowned inks of his time, he crafted signature inks within his collection of ink molds.

Ninth Generation: Matsui Motozuru (1799–1857) [Official Title: Izumi no Jo]

Granted the official title “Izumi no Jo,” he continued the family’s ink business under the peaceful and prosperous atmosphere of his era.

Tenth Generation: Matsui Motonaga (1828–1865) [Official Title: Tosa no Jo]

During the Meiji Restoration, he relinquished his official title and became “Purveyor to the Imperial Household Agency.” He renounced the title of Tosa no Jo during the Meiji Restoration.

Representative signature inks that proudly became the purveyor to the Imperial Household Agency.

Eleventh Generation: Matsui Motoyasu (1862–1931)

He served as the honorary mayor of Nara City and in the fourth year of the Taisho era, he reorganized the business into a corporate structure.

During the Meiji Restoration, he quickly dispatched diplomatic envoys nationwide in the industry, expanding the market with signature inks.

Twelfth Generation: Matsui Teitaro (1884–1952)

He served as a member of the House of Peers and as the honorary mayor of Nara City. He contributed to the ink-making industry.

Thirteenth Generation: Matsui Motohisa (1913–1967)

Even amidst the turbulent period of the end of World War II, he staunchly upheld the four-century-old prestigious business.

Fourteenth Generation: Matsui Gensho (1964–1997)

Passed on to the present, in 1985, after a hiatus, he successfully reproduced “Ikimatsu Matsukemuri” using a newly developed smoke extraction method.